I’ve been avoiding writing this post because there is huge potential for coming off as sanctimonious, “preachy”, or judging. Some people aren’t going to like it, but it's a post I have to write.

We don’t want to admit it, but the United States is hugely responsible for many adverse conditions in Haiti. Other Western countries also do their share of the pillaging—but that doesn’t let the U.S. off the hook because that’s like being a part of a gang who beats someone senseless, and pleading afterwards “But I wasn’t the only one hitting him.” Besides, my belief is that the U.S. owes more to Haiti because of its close proximity- it’s only a 1 ½ hour flight from Miami to Port au Prince.

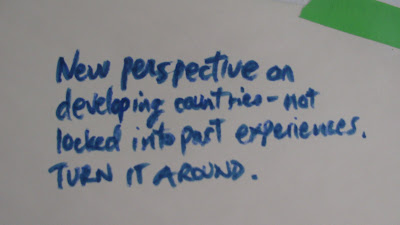

Anyway, there is this giant called the United States of America, and we have a functional government (I know, it sounds like an oxymoron) that very successfully looks out for our own interests. Then there is this pee-wee named Haiti that has suffered from a long string of dictators and failed leaders, and who most recently elected a Haitian pop star as their president, in an attempt to give someone a try who hasn’t come from a corrupt political career and thus may look at things differently. (Kind of like Arnold Schwarzenegger being elected in California)

So whenever there is a situation when the U.S. can benefit from something related to Haiti, the U.S. inevitably wins, and Haiti loses because the U.S grabs for what it wants like a two-year old in a sandbox. And the American people probably don’t even know this is happening because the trade agreements and political alliances happen on levels that we have no access to or that we find so boring and beyond our realm of influence that we don’t bother to keep informed about them.

But the fact is that I could physically see America’s adverse influence on Haiti while I was there. How?Rice. All over Haiti I saw 50 pound bags of rice in white canvas bags labeled “Made in the USA”.

Haitian farmers used to grow all their own rice, but for years buying imported U.S. rice has been cheaper than buying locally grown Haitian rice. So Haitians buy “Miami Rice” (get it?), Haitian rice farmers are out of a job, American rice farmers off-load their subsidized product, and the U.S. bags more money.

Chicken. Haiti has chickens running around all over the place. Sure they are scrawny—but chickens nonetheless. Tyson Foods takes the dark meat that Americans don’t want and exports it to Haiti. Guess who makes a lot of money on that? Tyson! Guess who loses out from raising local chickens? Haitians! To be fair, right after the earthquake in 2010 Tyson donated $250,000 to Haiti’s disaster relief efforts. But on the other hand, this is a company that makes hundreds of millions of dollars per quarter, so you be the judge on whether a $250K donation is significant or not.

Travel advisories. Some world travelers have long been distrustful of the United States’ travel warnings posted on State Department websites. “

The Department of State warns U.S. citizens of the risk of travel to…” It is suspected that there may be some less-than-truthful or some politically motivated reasons why American’s are discouraged from traveling to certain countries. One highly cynical theory- and I don’t know if it is true- is that U.S. Embassy employees get extra pay for living and working in a high risk area. Who writes the travel advisories? U.S. Embassy employees. Thus, to issue a warning about a certain country may work to the financial benefit of the person issuing the warning. My main point is that- partially due to travel advisories-- Haiti doesn’t seem to have any tourism. I’ve been to poor countries before but many of them have some sort of tourism infrastructure that brings in at least a little money. In Haiti I saw a few sub-par “resorts” along the beach where United Nations soldiers go to shed their camouflage and drink beer, but as a rule, tourism for pleasure is pretty non-existent in Haiti.

Volunteer Tourism. However, volunteer tourism (volunteering for a charitable cause) is rampant. And America spends a lot of money in Haiti through church groups, NGO’s, building projects, and medical clinics. But before we pat ourselves on the back too quickly, 12 months after the earthquake the Associated Press shared information that out of every $100 spent by U.S. organizations in Haiti, only $1.60 was won by Haitian contractors. In other words, Americans' charitable service to Haiti lines the pockets of Americans- not Haitians.

Trash. Port au Prince is covered with trash. There is so much trash because the Haitian government doesn’t have a handle on things like sanitation. Most Americans can’t wrap our heads around this reality because we enjoy regular sanitation pick ups once or twice a week. (In 2007 Oakland had a trash strike and the trash wasn’t picked up for weeks. Homeowners threw a tizzy fit, people were confronted with their waste consumption, and politicians were calling it a “serious health crisis.”) Not once did I see a public garbage can in Haiti. And even in places where there were huge trash bins, they were overflowing because the government doesn’t have someone pick them up regularly. I distinctly remember being in developing countries in the past, looking around at all the trash and thinking “if everyone is unemployed, why don’t they rally themselves to gather up all the trash and get rid of it?” But now I understand that there is nowhere for the trash to go.

But there is also trash in Haiti because American companies sell things to Haiti that exacerbates the trash situation. Haitian locals told us that in the last 15 years the trash has gotten worse in Haiti. Previously, Haitians used recyclable glass bottles for Coca Colas and other sugary drinks, which they would return back to the place of purchase. Now there are worthless, empty plastic bottles strewn everywhere. Previously, the Haitians wrapped street food in biodegradable banana leaves. Now there are Styrofoam containers tossed all over. Coca Cola and whoever manufactures and imports styrofoam gets money while the Haitian countryside gets litter.

Wood and gold. Haiti is completely deforested in part because long ago other countries took most of their wood to build houses in France and other lands. Canadian mining companies are scattered all over Haiti, taking Haiti’s natural resources and leaving massive soil erosion as a gift.

So the United States and other key Western countries are directly responsible for much of the tragedy and poverty in Haiti. Countries like the U.S. have what we have because countries like Haiti don’t have what they don’t have. Taking it up a notch- Melanie has what she needs (and wants) because a woman in Haiti doesn’t have what she needs. I'm currently sitting with that.